Yet again folks,

I return to the subject of restoring the old ringed stunt

engines from the 60’ and 70’s. These include the

Enya 45’s and Super Tigre 46 plus other capacity engines

from the same manufacturers. Some of these motors were quite

poor from new, while others, like the ST46, had great reputations,

but of which there was the occasional “Friday night

special”. Whatever, I have a bunch of them and have

slowly been getting them to run properly.

Where I have been really slow, is in realising that the individual

rings must be fitted to the cylinder using lapping techniques.

Once you have the cylinder bore right, you are not finished!

If you have purchased a ring, no matter from whom, you then

have the problem of whether the ring actually fits your cylinder,

including whether the ring gap is “correct”: whatever

the latter means!

Here is my Enya 45 6002 story. As reported previously on

this site, Richard Morrow did wonders for me in honing my

new Enya 45 6002 sleeve. After this, the motor ran fine, at

least until the public display day at Whiteman Park. Out of

4 flights, I got in 3 really nice motor runs, but on a hot

Sunday afternoon, the wretched thing would not start. Luckily,

Peter White was flying adjacent to me, thus masking my embarrassment.

It was apparent that the motor would not start hot, even

from just the sun shining on it. Not good: was this another

piston/cylinder problem? Well, I reckon all problems are piston/cylinder

ones, unless proven otherwise; so I started to think about

pulling the motor down, yet again. However, fate stepped in,

for once, smiling upon me!

We received an invite to Stumax’s wedding in Sydney:

this was too good an offer to refuse, so we booked on Virgin

and were off out here: Perth, the most isolated city in the

world. Not only that, but Andrew Heath had organised some

Acrolap barrel-laps for me: they were arriving in Bowen Mountain

about the same time, so we could kill at least two birds with

one stone.

But it was better than that. Andrew knew I had a new lathe,

so out of the blue he says “Stu, would you like to see

how to make piston rings?” Do pigs have bums? Is Britney

an airhead? Would I? Hell yes! So down to his workshop, for

an education in technique you could die for.

But did I need a new ring for my gallant old Enya? Only one

way to find out, I pulled it down and measured the ring gap.

Would you believe .013”? It should have been about .003”.

Could this be where the compression was disappearing? Andrew

showed me an ST60 he had fitted with a new ring. It had compression

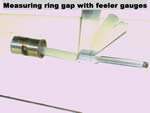

like a Rothwell diesel. I was astonished. By the way, to measure

ring gap, you need to remove the ring from the piston, then

insert the ring into the bore: feeler gauges complete the

method. The ring may be correctly “squared” with

the bore by nudging it into place with the piston skirt.

Closer examination of the Enya ring was interesting. No doubt

about it, this was a well made item. The seat against the

sleeve was excellent. The seat against the piston groove was

bright and shiny, while the pressure side was dark from the

hot gases. Ring tension was good: it was only the ring gap

that let me down, not least because we had re-honed the sleeve,

no doubt increasing the bore by a small amount.

Nevertheless, it was time to make my own ring, matched to

the sleeve in my particular engine. Andrew has agreed to reveal

his secrets, so fasten your seat belts, this is an exciting

ride.

First off, you need some cast iron rod. Blackwoods supply

a grade of Meehanite numbered “4E”. All sorts

of funny metallurgy there: but this grade is the one to use.

I popped it in the chuck, then machined the inner diameter

to 20mm, the outer diameter to 22.27mm. That outer diameter

was the best I could do to make the sleeve just slide onto

the latent ring. In other words, the ring is machined to exact

size, then parted off to exact depth, in this case 1.00mm.

The ring can now be slid down into the bore: if you have

done it right, this is a very close fit. Of course, you can’t

get it onto the piston yet: the ring has to be “cracked”

and opened out. I’d heard of this “cracking”

process before: guys were wrecking 2 out of every 3 rings

they made, as the cast iron, being brittle, is contrary to

handle. But Andrew had this licked. First you made a slight

nick on the inner side of the ring. The ring was then mounted

in a vice, with the nick hard up against the jaws. I use a

precision vice with smooth jaws, which style jaws avoid marking

the ring. This gave a nice stress concentration, so that with

the overhanging ring held neatly in the jaws of a shifter,

the snap would occur exactly as desired; with a minimal amount

of bending back and forth. In my case, it was once forth and

once back, by the smallest of deflections, lo; there was the

crack. I hardly knew it had happened!

With the crack formed, an attempt was made to again place

the ring in the sleeve. This failed. Evidently, there is distortion

of the metal at the crack, which prevents the ring from closing

to its original diameter. So the next trick is to clean up

this distortion, then set the ring gap. A piece of carborundum

paper (wet-and-dry) of about 1200 grade (Andrew used 2000

grade, doubled over to dress both sides of the gap at the

same time. This gives a better seal) is inserted into the

gap, then worked back and forth a few times. The ring probably

still won’t go in, so the abrasion is continued by trial

and error until the ring just goes in. At this point, you

need to decide what width the gap should be. A rule of thumb

exists: the gap should be .003” per inch of bore diameter.

I don’t know where this came from, so it’s an

area for experimentation.

I recall an article in FM by Larry Scarinzi, referring to

the ST60 in his “Blue Angel” stunter. Evidently

the weather was hot at the US Nats that year: he thought his

overheating problems were related to ring gap being too close.

Quite possibly, so that is something to watch.

Next step is intended to tension the ring. The idea seems

to be that the ring must mechanically press on the cylinder

walls to provide the seal. This is achieved by inserting a

spacer into the ring gap, in order to force it open. By heating

the ring to either red heat or, in my case, 500C, for stress

relief, then the ring takes a permanent set. Andrew has an

electric oven top, on which one of the elements glows red

hot. The ring plus spacer is placed on this element, the element

allowed to heat briefly to red emissivity, then allowed to

cool in air.

Most probably, red heat also causes the cast iron to harden

further. I do not have such an oven, so I bought an electric

hot plate from the Supermarket for $40. The smaller of the

2 elements was 800 watts: regrettably, it would not glow red

hot as I had hoped. Instead it got to only 350C, the maximum

setting on the thermostat. As it happened, this thermostat

could be “adjusted” by simply altering its upper-limit

detent. This got it up to 500C, which was worth a try. The

temperature stress-relief range for cast iron is 450 to 550C,

so this was at least promising.

Andrew sets the gap after heat treating. He uses red heat,

so I guess that is better in case the heat changes the dimensions

of the ring in any way. With the milder 500C treatment, the

gap seemed to be the same after heat treatment. Regrettably,

I forgot to measure the final gap; too late now.

My first attempt using a 2mm spreader, lead to a space of

1.12mm: the ring returned partially to its original shape.

A second attempt with a 3mm spacer gave a space of 2.16mm,

which was taken to be acceptable. The ring did not have the

same “springiness” as the original Enya ring,

but there was no going back now. Only time would tell if the

ring temper was OK for use over time. The clever thing in

all this is that the ring, when compressed to load it into

the cylinder, retains accurately its original circular shape.

This completed the ring, except for some de-burring to remove

rough edges that would catch on the piston during reassembly,

or else score the sleeve. The ring went onto the piston with

no problems, even though I had increased its width from the

original 1.02mm to 1.13mm. Care is needed here to avoid excessive

bending of the ring, thereby introducing a new, unwanted,

permanent set. I do it by inserting one end of the ring gap

into the piston groove, then attempt to use this as a lead

to “winding in” the next piece. Seems to work.

My camera hates doing close-ups; otherwise I would include

a photo.

Well it all went back together, so it was on to the test

bench for 30 minutes bedding in. The ring developed some nice

rub marks during this time. Testing of the hot compression

as soon as the motor stopped suggested that a considerable

improvement had been made with the seal.

In a howling Easterly gale, at about 33C, the “Heart

of Gold” leapt out of the stooge, a bit lean, but otherwise

sweet. Engine had started first flick from a venturi prime,

so I was pretty happy with that. Second flight was a first

flick start, no prime, after sitting in the sun! Well, one

Swallow doth not a summer make, but that looked like a pretty

good result to me.

My thanks to Andrew Heath for sharing his secrets: also for

giving me some Meehanite to make the ring. By the way, if

Bowen Mountain is not paradise, then its only one short hop

away!

|